Hearing in the Underwater World

By Steve Quinn

We anglers tend to interpret animal behavior from our own point of view and sensory abilities. Though our vision pales in comparison to birds and some animals, we rely on sight for nearly all our activities. The Bill Lewis Company has sold more than 150 colors of their Rat-L-Trap because anglers tend to focus on lures’ visual appeal. Professional bass anglers worry over differences in tint among plastic worms labelled “green pumpkin,” as if bass could tell the difference. When we snorkel or scuba dive, we hear nothing but our own exhalations. For centuries, mariners and scientists generally regarded the aquatic world as quiet, as referenced by Jacques Yves Cousteau’s famed film, “Silent World,” released in 1956. Since then, scientists have learned a lot about sound under water and how fish species respond to it. And as anglers, this can correlate to our performance on the water, or lack thereof.

Sound Science

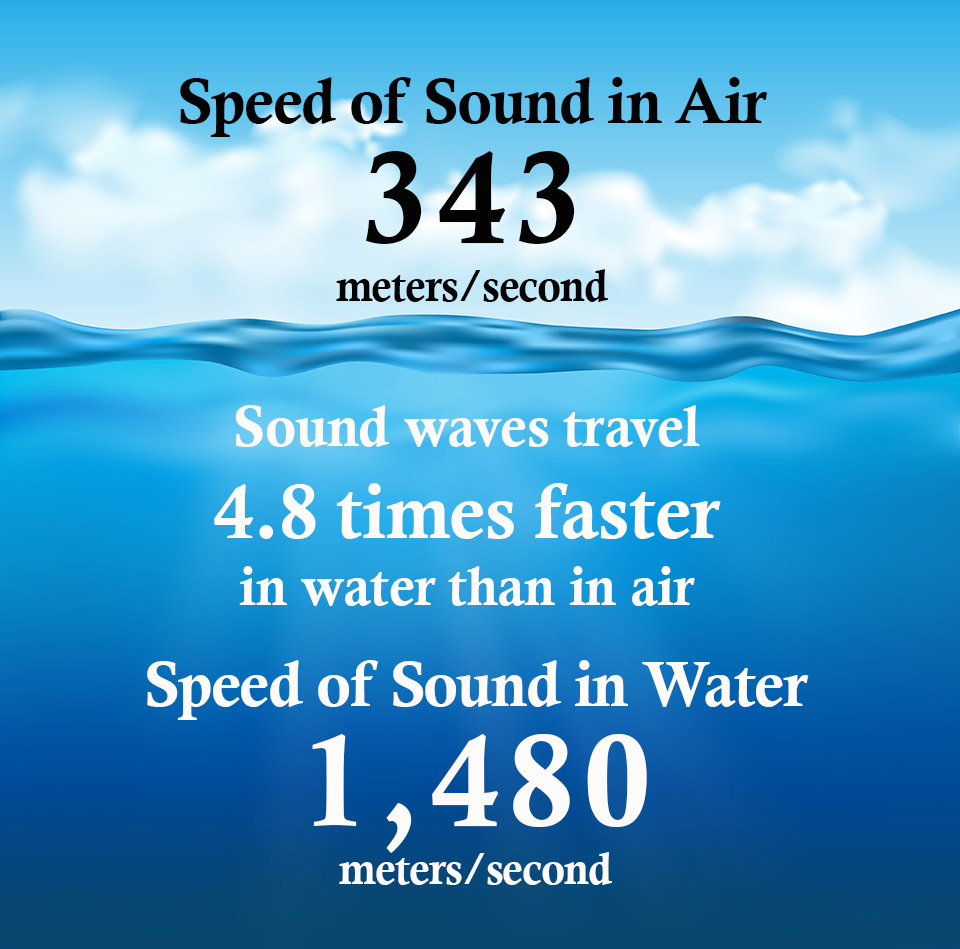

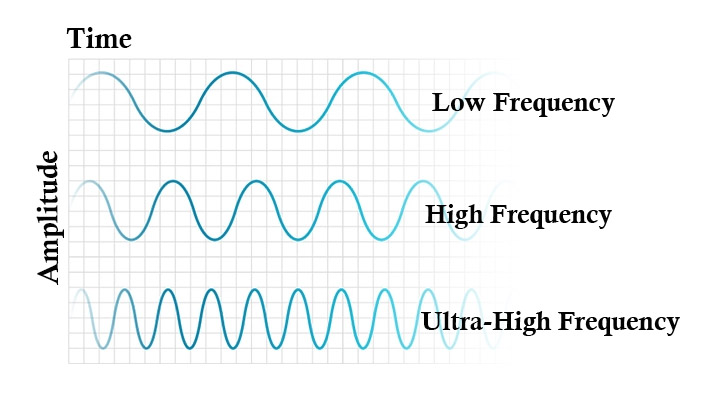

Physics informs us that because molecules in water are packed more closely together than they are in air, motional energy is transferred faster, and sound waves travel 4.8 times faster in water than in air. Lower-frequency sounds can travel amazingly far. In his book, “Knowing Bass,” long-time bass sensory researcher Dr. Keith Jones noted that when the Soviet Union launched their “Alpha-class” submarines off the coast of Norway in the 1970s, a U.S. Naval station in Bermuda picked up the sounds from 4,000 miles away.

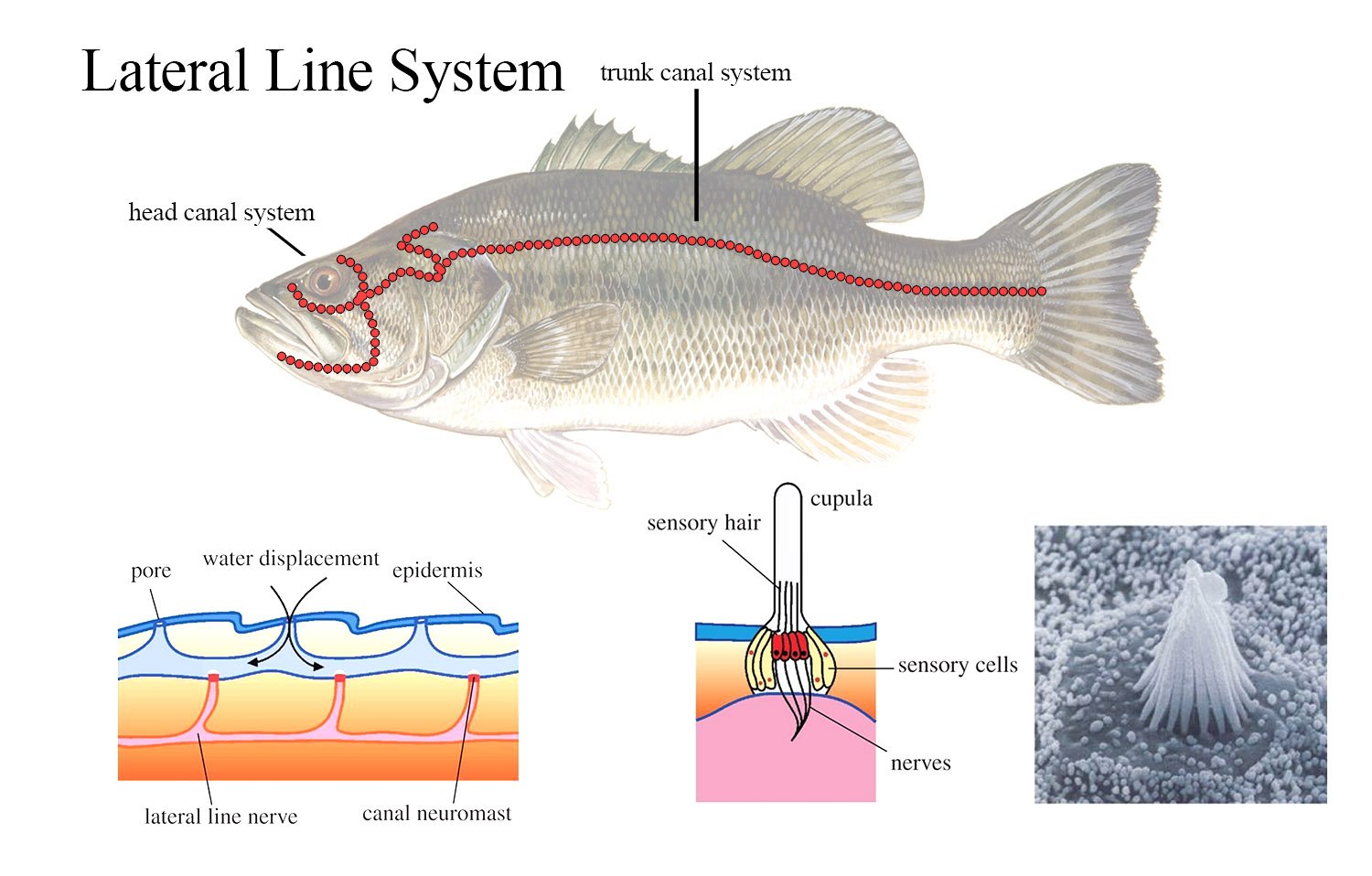

It is important to note that water movement, such as from fin movements, water currents, or lures is an acoustic phenomenon involving pressure waves. This characteristic of sound in water has led to the evolution of a lateral-line system in fish and aquatic amphibians to interpret low-frequency underwater vibrations and sounds. The lateral line works with the inner ears to decipher the direction and meaning of sounds. This organ can be seen on the sides of many fish species as a series of pores from the head to the caudal fin.

How Fish Hear

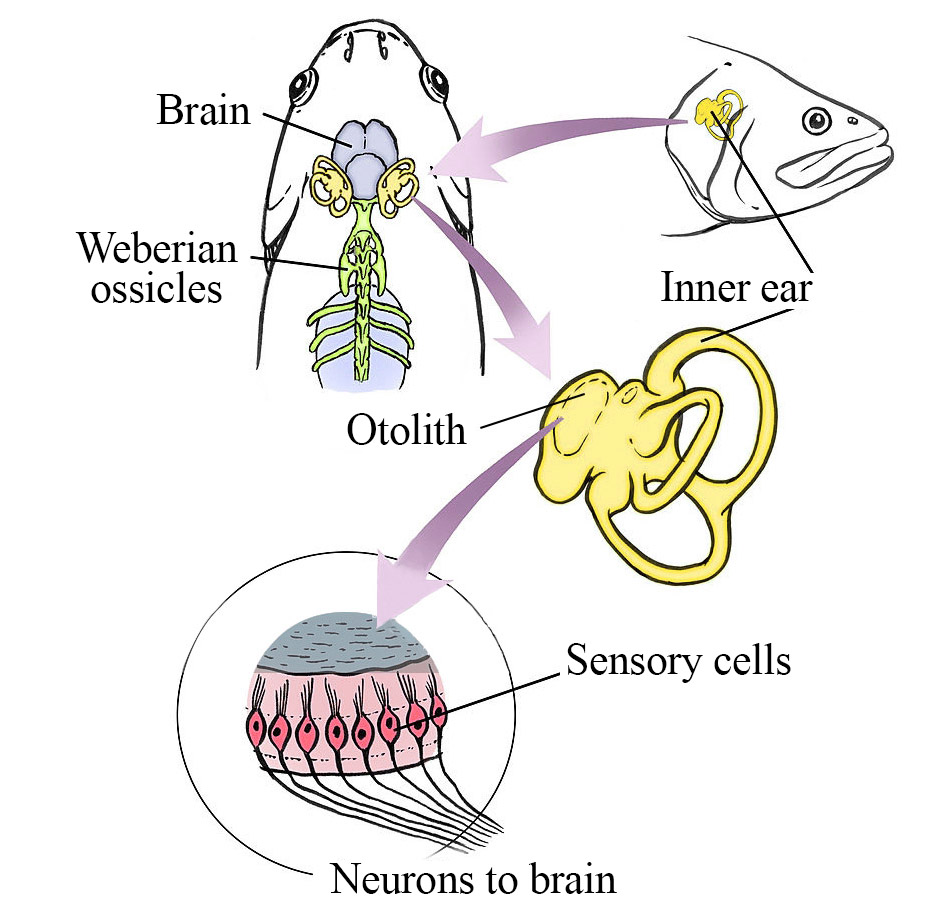

Because of the need for a streamlined shape, fish lack an outer ear that funnels sound waves to the inner ear. And because they live in an aquatic environment, they don’t need a middle ear to transduce compression waves in air into the movement of fluid that stimulates hair cells in the inner ear, leading to hearing. The inner ears of fish are similar to ours, with a system of ducts and chambers and containing ear stones called otoliths.

Because fish are about the same density as water, sound waves move through their bodies at about the same amplitude and frequency as through water. Otoliths are about three times as dense as the fish’s body, however. When sound waves contact an otolith, it vibrates at a different rate from the tissues around it. Sensory cells bend in a particular way, sending a sound message to the brain.

As head of fish research at Berkley, Dr. Jones studied how fish use their senses for feeding. His experiments on taste and smell in bass, trout, and catfish led to development of many successful lures. He studied hearing as well, but didn’t conduct experiments to define the sensitivity and range of their capabilities and he notes that few studies have focused on the sounds fish hear most easily and how their brain interprets them.

“A key study was done by Dr. Don McCoy at the University of Kentucky,” Jones reports. “He trained largemouth bass to respond to sounds by giving them a slight electric shock to encourage them to move across a barrier. He then tested different sound frequencies to learn which ones bass could detect and built a hearing curve based on the results.”

“He found that bass have a narrow range of sound sensitivity, with a peak around 100 cycles per second, which is quite low. Bass hearing is weak above 200 cycles per second, and sounds above 600 aren’t heard. This range of hearing is common for fish that are hearing generalists, which include most predatory gamefish.”

“Humans, in contrast, hear from 20 to 20,000 cycles per second. Hearing specialists, such as minnows and catfish, have greater hearing range, thanks to their ability to amplify sounds resonating in their gas bladder with a special skeletal structure called Weberian ossicles. Species that lack this adaptation hear only low-frequency sounds,” Jones concludes.

Head of fish research at Berkley, Pure Fishing, Dr. Keith Jones.

Using Sound to Catch Fish

Though scientists understood characteristics of sound underwater, anglers and lure designers gave it little thought until the 1950s. In-Fisherman Editor in Chief Doug Stange recalls coming across a “fish call” in a Herter’s catalog in the late 1950s. “As I recall, it was basically a small can with BBs inside, attached to a string that allowed it to be lowered into the depths,” Stange reports. “You activated the call by pulling the string, which shook the can. Fishing from a public dock on Lake Okoboji in Iowa, I became convinced it worked. When the bite slowed, its owner would shake it and the perch and sheepshead would start biting again.”

The development of sound-producing lures came about rather serendipitously. Famed lure designer Cotton Cordell is credited with making the first rattling lipless lure, the Cordell Hot Spot. “In the late 1960s, I designed the Hot Spot as a plastic version of the Gay Blade, a blade-bait that was popular at the time,” he recalled. “I placed a lead slug in the lure’s nose for correct balance and increased casting distance, but some came loose and rattled inside.”

“The Hot Spot was selling well, but we learned anglers were rapping them on the counter to find the ones where the slug had come unglued. They’d buy the  rattling ones since they worked better. Rattlin’ crankbaits were an accident, but I soon revised the design so all Hot Spots rattled.”

rattling ones since they worked better. Rattlin’ crankbaits were an accident, but I soon revised the design so all Hot Spots rattled.”

Bill Lewis built a lipless bait to capitalize on sound production as well, which he called a Rat-L-Trap. Wes Higgins, President of Bill Lewis Lures, recalls its origins: “Lewis built one and loaded shotgun pellets into the body so it would run upright. He noted how loud it was, and bass went wild for it. To promote it, he gave Rat-L-Traps to fishing guides or traded them two ‘Traps for their favorite lure. The rest is history, as the Rat-L-Trap soared in popularity and remains a top seller 50 years later.”

Success with Sound

Dr. Jones offers a scenario of how fish use sound in feeding: “Fish’s inner ears and lateral lines are each tuned to different frequencies,” he says. “They act together to allow fish to form a composite interpretation of sounds around it.” He notes potential stages in predation via sound. “The inner ears do most of the work in cluing a bass into sounds generated more than a few body lengths away. Fish hear better in deep water, since sound waves can travel farther. They instinctively analyze the intensity, frequency, and other aspects of a sound to determine whether it might signal food or else danger. Most fish that often inhabit murky waters won’t move far to track sounds, especially if vision is limited. When a bass is close to a target, it studies it with the lateral line as well as visually. If it seems edible, it’s attacked.” You can observe this behavior as fish slowly approach potential prey and tilt their heads toward it. This allows the lateral line to analyze low-frequency sounds or vibrations, and lets the fish fix both eyes on the object, increasing depth perception. If it passes the test, it often strikes.

A key question is, “How closely do rattling lures match the sound frequency range fish hear best?” Unfortunately, answers to those questions are elusive. Aside from Berkley’s research lab, facilities to test this question aren’t commonly available. Moreover, it seems anglers want rattling lures, even if their effects on fish are unknown. Only a few investigations have been conducted of the sound frequencies lures produce and how well they match acoustic perception by predatory fish. They’ve generally found that the loudest sounds created by rattling crankbaits are high-pitched; mostly over 2,000 Hz, which is beyond the hearing range of most game fish. Studies show that some lures produce a wide range of sound frequencies, but lower-frequency sounds are much weaker, so their efficacy as an attractor is questionable, at least for fish more than a few feet away from the source. Predators seem tuned to the low-frequency vibrations created by the movements of prey fish and invertebrates such as crayfish.

Sound Lure Choices

In recent years, companies have begun to offer more lures that produced dominant lower-frequency sounds by using a few larger BBs or metal slugs. Anglers also began to recognize that especially in heavily

fished waters; lures that didn’t rattle often were more effective than loud ones. Water clarity and fish activity also seem linked to sound’s effectiveness. For less active fish in clear water, rattles could be detrimental to success.

Booyah Lure Company added a low-frequency lipless lure, the One Knocker Spot, with a single large tungsten rattler that produces a loud and steady thump as it’s retrieved, and it’s proven a popular addition. Rapala engineers designed the Clackin’ Rap and Clackin’ Crank with a unique rattle chamber based on a pair of metal discs on each side of the lure that clack against the plastic body as it’s reeled. And their DT series of diving baits has a small rattle chamber encased in the balsa body. Strike King recently added the Red Eye Shad Tungsten 2-Tap, using a tungsten bead to create a low-frequency tapping sound that’s proven highly effective. It complements the standard Red Eye Shad, which produces higher-pitched sounds. The precise frequencies these lures produce haven’t been evaluated to my knowledge.

In some situations, I’ve been convinced rattling jigs or soft baits with a glass rattle chamber stuffed inside attracted more bites than plain models. Other anglers obviously have seen similar effects, since they continue to be good sellers. While many questions remain about how we can best use sound-producing lures to excite fish, this topic will be an important one as creative lure designers search for the next best thing. Stay tuned!