All Eyes on Alaska

By Steve Quinn

I’ve never talked to any first-time visitor to Alaska who wasn’t astounded by its incredible scenery, challenging landscape, bountiful wildlife, and uncountable numbers of big fish. Every angler owes him- or herself a trip to America’s 49th state. It’s the largest one by far, covering 20 percent of the land mass of the rest of the US—about 1,420 miles north to south and 2,500 miles east to west. If it was a separate country, it would be the world’s seventh largest! It contains our nation’s foremost natural resources as well. It’s safe to say that no human “knows” Alaska; all of us, even lifetime inhabitants, feel fortunate to get a taste of it.

A Bit of History

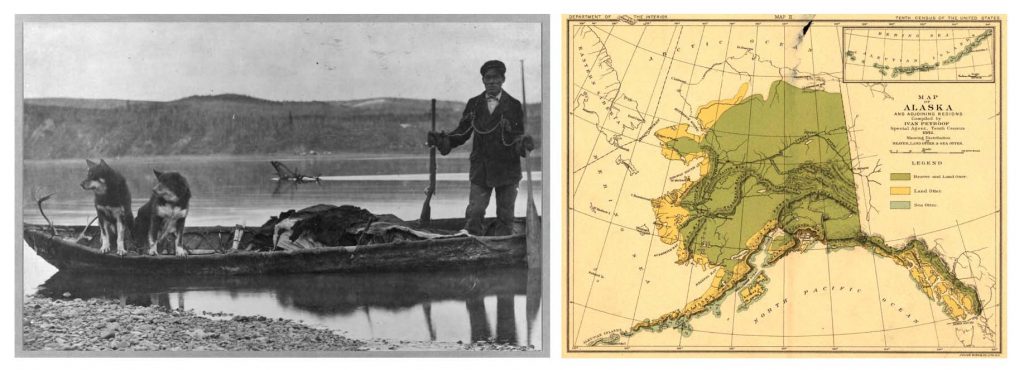

Over 15,000 years ago, early people crossed the Bering Land Bridge from Asia during the last Ice Age, settling along the coast and gradually moving inland where they fished and hunted in a subsistence manner. In the early 18th century, Russian explorers ventured across the Bering Sea, the first Europeans to set foot there. It’s less than 75 miles from the westernmost town in Alaska to the Russian border.

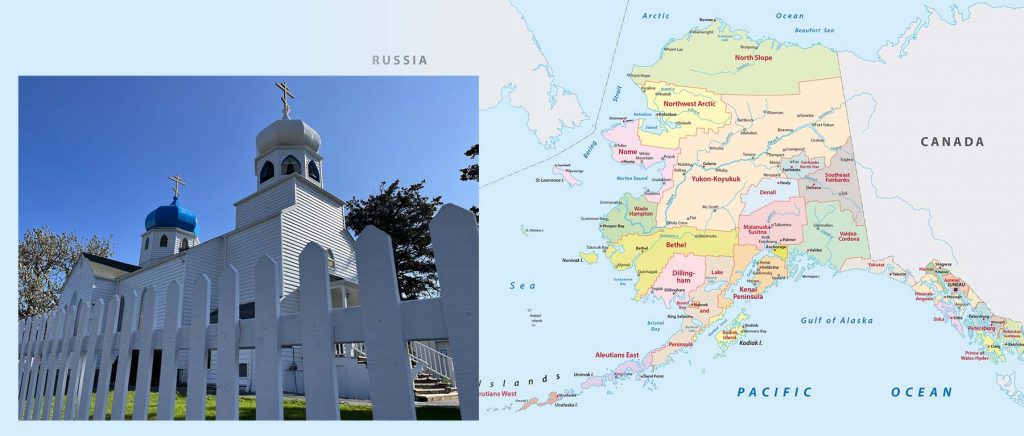

Furs were the major draw for the Russians and early European settlers, especially sea otter pelts with their thick fur, considered ideal for coats and hats. In 1784, Grigory Shelikhov arrived on Kodiak Island and began operating a fur-trading company and established the first permanent European settlement. Towns on the mainland followed and in 1795, Alexander Baranov sailed into Sitka Sound and claimed it for Russia. Shelikhov had hired him to operate his fur trade and Sitka became the colonial capital in part because of its abundant sea otters. It remained the capital of the Alaskan Territory after purchase by the U.S. In the 1790s, missionaries of the Russian Orthodox Christian faith arrived and built missions and churches, some of which exist today, the most visible trace of Russia’s colonial period, in addition to the map that shows many Russian names of islands and towns.

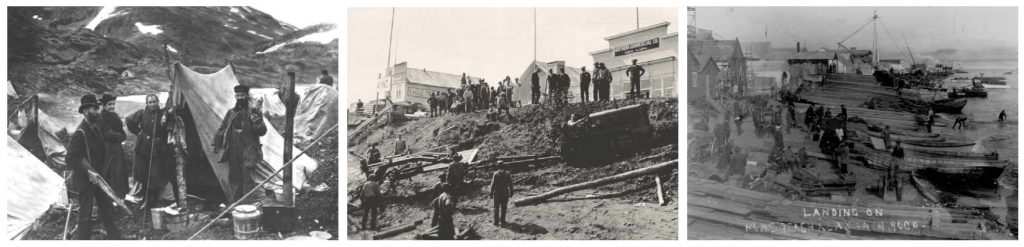

Path to Statehood: In 1859, the challenging environment and reduced otter numbers, as well as debts from its defeat in the Crimean War, led Czar Alexander II and the Russian government to offer the territory to the United States. Secretary of State William H. Seward was enthusiastic about this opportunity for westward expansion. In Washington, however, doubters made their opposition known. The Civil War delayed the sale, but a deal was struck in 1867, the U.S. paying $7.2 million in exchange for what would become the most valuable piece of land on the continent. Opponents of the Alaska Purchase called it “Seward’s Icebox” until the Klondike Gold Strike in 1896 convinced the most dubious legislators and citizens that it was indeed a valuable addition to the young country.

After World War II, US President Eisenhower was in favor of statehood, but details about the transfer of federal lands to the state had to be sorted out. Moreover, there were concerns about national security during the height of the Cold War as Russia loomed so close by. But he signed the official proclamation in 1958, making Alaska our 49th state.

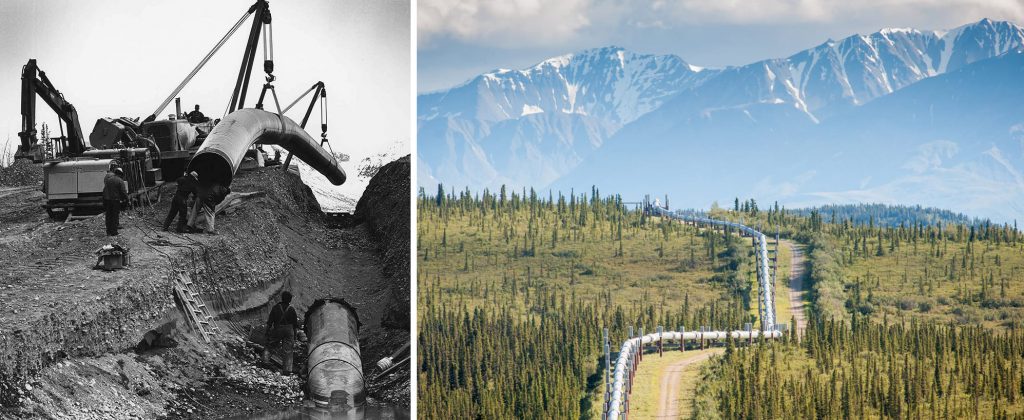

The Pipeline: Following the commercial discovery of oil in Prudhoe Bay in 1968, oil companies gained permission to build the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, completed in 1977. Ages before that, Inupiat people had used the seepage they found for fuel and light. Today, a 48-inch diameter tube runs 800 miles from the North Slope to the port of Valdez in south-central Alaska. Permafrost presented particular challenges to the project, which brought many thousands of well-paid workers, creating a boom-town atmosphere.

The project was highly controversial for potential environmental impacts and native land-rights concerns. Over the years, it’s suffered leaks that caused damage, though fortunately no catastrophic ones. The state receives large royalties from oil companies, while native groups and other citizens also receive annual payments. Its future is murky as oil production has diminished, falling from 1.5 million barrels a day in 1980 to about 500,000 today.

The 2020 census counted 733,000 Alaskans, including 133,000 Alaska Natives of numerous tribes, cooperatives, and village groups. Yup’ik, Tlingit, Inupiat, Aleuts, Naparymiut, and Athabascans are the largest groups. Many remain in traditional villages, adhering to cultures and languages, while others have gradually mixed into the population. As in other parts of the Americas, interest in maintaining native cultures and languages is growing throughout Alaska.

An Abundance of Fishes

Fishing was far from the forefront in the early days, though native peoples relied on salmon runs and nearshore marine fisheries, in addition to hunting seals, walruses, caribou, moose, bear, and smaller animals to sustain themselves through the long winter and provide clothing.

Today, the impacts of sportfishing are massive. The most recent available economic survey (2009) estimated about $1.4 billion dollars in angler expenditures, supporting over 3,000 jobs and adding $22 million in taxes alone. That has likely doubled since. Alaska’s commercial salmon fishery is important as well, averaging 740 million pounds annually, valued at $397 million through the early decades of the 21st century. Other important commercial species are walleye, pollock, Pacific cod, halibut, crab, and sablefish.

I’ve been fortunate to visit Alaska quite a few times, though far less than many anglers, researchers, hunters, and wildlife watchers. It’s a popular destination for cruise ships for its majestic scenery as well as tourist activities ashore. My brother Tom, a fishery biologist and professor at the University of Washington, has often served as my guide, though he readily admits he’s seen but a tiny fraction of its offerings. But for over three decades, his position as Director of the university’s Alaska Research Program brought him to various locations for summer study. Our trips have revealed amazing and varied locations with fishing unimaginable to anglers in the ”Lower 48.” I spent several days at one of Tom’s research camps where we fished around Chignik and also enjoyed a wonderful day of bear-watching at Brooks Falls in Katmai National Park, where crowds of tourists from around the world visit to observe and photograph grizzly bears as they gorge on leaping salmon, feed their cubs, and play, oblivious to humans on a set of platforms and walkways that separate the species.

Salmon and Trout

Without a doubt, salmon fishing is inextricably linked to Alaska, as these majestic fish have provided food for thousands of years and been important cultural symbols revealed in native art, as well as world-class recreational opportunities in recent times. Its rivers provide wonderful habitat for the complex life histories of these special fish and support excellent fisheries up and down the coast. Modern Alaskans, a diverse ethnic population, revere salmon for their fascinating life histories as well as their economic value, making them an icon, as well as the state fish, the Chinook.

Alaska contains more than 12,000 rivers that comprise about 40 percent of the water resources of the entire United States. Most of them host runs of anadromous salmon, generally beginning with sockeye that arrive in early summer, though Chinook precede them in some systems, followed by pink, coho, and chum. The timing of runs and conditions vary greatly along the coast, due to genetic variation and differing climate from north to south, from Southeast Alaska into Arctic waters. Unlike the salmon rivers of California, Oregon, and Washington, damming has not been a prohibitive factor in salmon production, as relatively few exist, and most are on upstream stretches not critical to salmon reproduction on a broad scale, though local effects are noted.

Chinook or king salmon are the least abundant but largest Pacific salmon, and like many salmonids, demonstrate a marvelous variety of life histories from the behavior of hatchling fry to adult migrations. Some populations in large rivers have spring-migrating adults that spend summer in freshwater before spawning in fall. In other systems, adults enter streams in the fall. Though not feeding at all, they’re popular as aggressive biters on lures and big gaudy flies and make powerful runs. Some rivers, such as the famous Kenai, host occasional fish over 60 pounds, including the 97 1/4-pound IGFA All-Tackle World Record caught in 1985. Coho or silver salmon also are large, adults often running from 8 to 12 pounds. Many migrate into small creeks in late summer, providing wild action in shallow water, as they leap spectacularly and may run around your waders.

The Marine Scene

I’ll never forget the 40-minute battle to haul up my personal best 210-pound halibut from 430 feet of water off Sitka in southeastern Alaska, and the exhausted exhilaration that accompanied its landing. We’d started the day a few hundred yards outside a river mouth, with three or four anglers hooked up simultaneously with streaking Chinooks. Salmon feed in nearshore ocean waters during the spring and summer before undertaking spawning runs, making for sensational boat-fishing. Once we’d approached our limit of catches that day, we steamed offshore to bottom-fish. On other trips, we’ve caught halibut just a long cast from shore and Tom accomplished the unusual feat of halibut on a fly. The variety of fishing opportunities cannot be described in a large book, so you just must start exploring to plan your next trip.

Inland Opportunities

While some anadromous species travel far into the interior before spawning and dying in the case of salmon, and potentially returning to sea for another year, in the case of steelhead, many rivers and lakes contain freshwater populations of rainbow trout and Dolly Varden, including the Kenai. They provide opportunities for fast fall fishing for hefty trout once the salmon fishers have gone home. Shore anglers wade among salmon carcasses, while drift boats head slowly downstream, stopping at key spots to cast before taking out at downstream accesses.

Alaska also is home to some of North America’s biggest northern pike, especially in the Yukon River drainage where they inhabit backwaters and grassy sloughs. Pike over 50 inches and 30 pounds aren’t uncommon there. The state record is 38 pounds, caught in the Innoko River, a tributary of the Yukon. Elsewhere, particularly around Anchorage, the Kenai Peninsula, and Susitna Valley, they’ve been illegally imported and represent an invasive species that threatens trout and salmon populations, leading the Alaska Department of Fish & Game to attempt eradication.

Anglers seeking a unique experience can travel to remote rivers in the southern part of the Brooks Range, northwest of Fairbanks, to catch sheefish or inconnu, the largest member of the whitefish family. These ghosts of the Arctic undertake long seasonal migrations to their fall spawning grounds. The IGFA All-Tackle World Record of 53 pounds was taken in the Pah River, while nearly all IGFA line-class records have come from the Kobuk and Holitna rivers, where they feed heavily in late summer. Sheefish readily strike lures and flies with 10- and 12-weight fly rods or conventional tackle with 12- to 20-pound line being effective. Several outfitters operate from houseboats to provide mobility in these river systems.

Kodiak Island

Kodiak Island lying about 30 miles from the mainland across the Shelikov Straight is a go-to getaway for tourist anglers, with a fascinating history and a rich abundance of natural resources. It’s 99 miles long, the second-largest island in the US. Even its name suggests adventure, perhaps due to the term used for the population of huge grizzly bears that are so abundant there. And old-timers won’t forget the name of their trusty Kodak cameras that helped make photography such a popular hobby. Indeed, don’t skimp on photographic evidence of Kodiak’s wonders when you visit.

Long the ancestral home of the Sugpiaq people of the Alutiiq Alaska Nation, its late 18th-century history mirrored the mainland. Shelikhov settled there in 1784, in what’s now known as Old Harbor. Following his massacre of hundreds of natives, he forced local men to hunt sea otters for their pelts, while their families were left behind to fend for themselves or starve. About 10 years later, he imported Russian craftsmen to work in shipyards and factories as a form of indentured servants.

While life is far more peaceful today, it’s a harsh environment, even by Alaska standards. In 1912, the volcano Novorupta erupted 100 miles Northwest of Kodiak and volcanic ash rained for days, bringing darkness and suffocating air that caused animals to starve to death and clogged streams, causing a huge crash in salmon production that lasted almost 10 years. In 1964, an earthquake and resulting tsunami destroyed much of the waterfront, business district, and several villages.

Today, most of the southern part of the island lies within the 1.9-million acre Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, while the northern and eastern portions are mountainous and heavily forested. Its location puts it in a prime location for excellent saltwater fishing close to shore, where charter boats tangle with halibut, lingcod, rockfish, Pacific cod, and more. Streams lying along the road system truly teem with salmon as waves of different species feed off the coast and then come inland to spawn. Kodiak also features expansive sand beaches surrounded by rocky promontories, and during our trip last summer, we enjoyed fast shore-fishing for coho off the beach as waves pummeled us, action that reminded me of surf-casting for striped bass.

Most of the island is accessible only by boat or air, called the Remote Zone, so residents are a resourceful and independent lot who excel at many skills. Small aircraft and charter boats offer trips to some of these remote waters that see little fishing pressure. Kodiak’s airport has regular service from Anchorage, about 250 miles northeast, as well as local flights to other mainland towns, though delays due to weather are not uncommon, as occurred for our visit.

Get There

If you’ve never visited Alaska, you owe it to yourself as an angler and explorer to visit as often as you can. It’s a short season, so book soon since charter operations fill quickly. And if you’re a frequent visitor, I’m jealous since you have so many more tales to tell.