IGFA Contributes to War Effort

By Mike Rivkin, author of Big Game Fishing Headquarters: A History of the IGFA

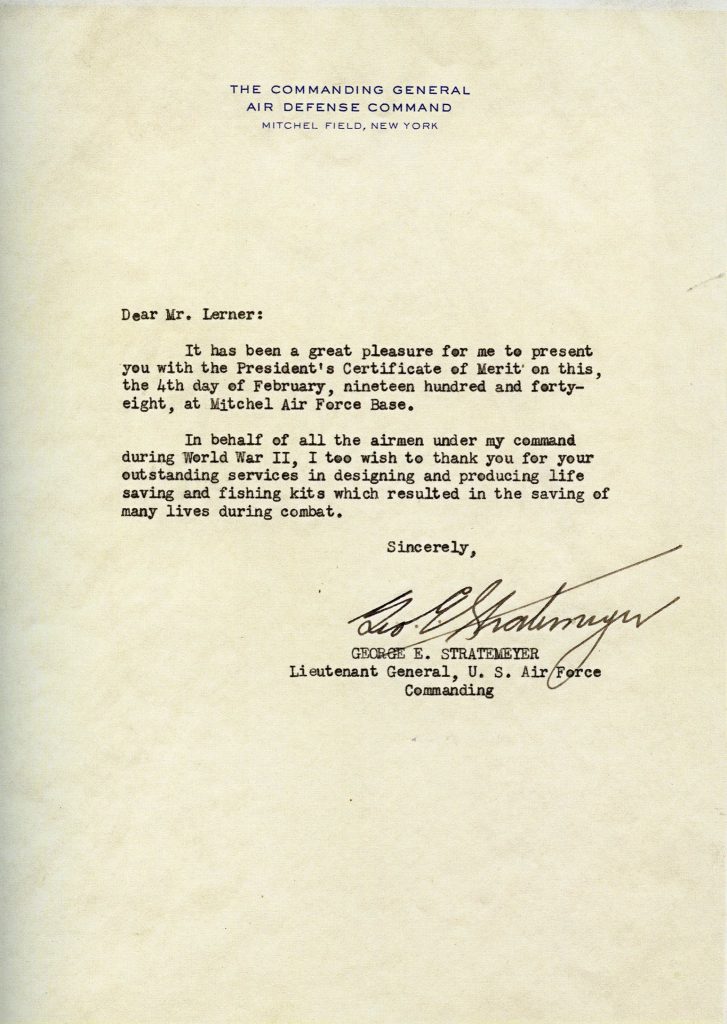

Over our 80-year history, the IGFA has persevered through global struggles like the recent COVID-19 pandemic thanks to passionate anglers like you. The IGFA was founded on the eve of World War II in 1939, and unbeknownst by many, played a crucial role during this global crisis. Led by its founder Michael Lerner, the IGFA assisted the Allied forces during World War II with the design of survival kits for servicemen stranded or adrift at sea. Let’s learn more about this significant, yet relatively unknown part of the IGFA’s history.

Over our 80-year history, the IGFA has persevered through global struggles like the recent COVID-19 pandemic thanks to passionate anglers like you. The IGFA was founded on the eve of World War II in 1939, and unbeknownst by many, played a crucial role during this global crisis. Led by its founder Michael Lerner, the IGFA assisted the Allied forces during World War II with the design of survival kits for servicemen stranded or adrift at sea. Let’s learn more about this significant, yet relatively unknown part of the IGFA’s history.

Considerable research on the edibility of saltwater fish had determined that all but four relatively rare species could be safely eaten either cooked or raw. It was also discovered how lymphatic fluid could be extracted from the flesh of raw fish and substituted for water. Indeed, subsequent tests showed that sailors could easily survive for 10 days or more while drinking nothing else. With this information in hand, a technical committee was formed in late 1942, with Lerner at its head, to address the need for an improved emergency survival kit.

Its members were among the most accomplished anglers of the day – Michael Lerner, Kip Farrington, Philip Wylie, Captain Eddie Wall, Julian Crandall, and Captain Bill Hatch – and they immediately went to work.

Recognizing the vital and immediate importance of its charge, the group interviewed hundreds of airmen and sailors with the first-hand experience of being abandoned at sea. Lerner himself spent months testing various elements off the coast of Florida, and all committee members participated in extensive sea trials. In February of 1943, the new kit was formally adopted by the US Navy and shortly thereafter by the other maritime services. Instead of the heavy tarred lines used previously, Lerner introduced the concept of an emergency vest that included hooks of various sizes, assorted baits, a knife, sharpening stone, net, harpoon, and (most importantly) instructions for use. Packed in a sealed coffee can and weighing about three pounds, each element in the kit was carefully described and its use outlined in a variety of different settings. The pursuit of fish over 25-kilograms (50-pounds) was discouraged since a loss of gear could be catastrophic. Nevertheless, servicemen were instructed as to the capture of birds, bait, turtles, crawfish, and anything else that might keep them alive.

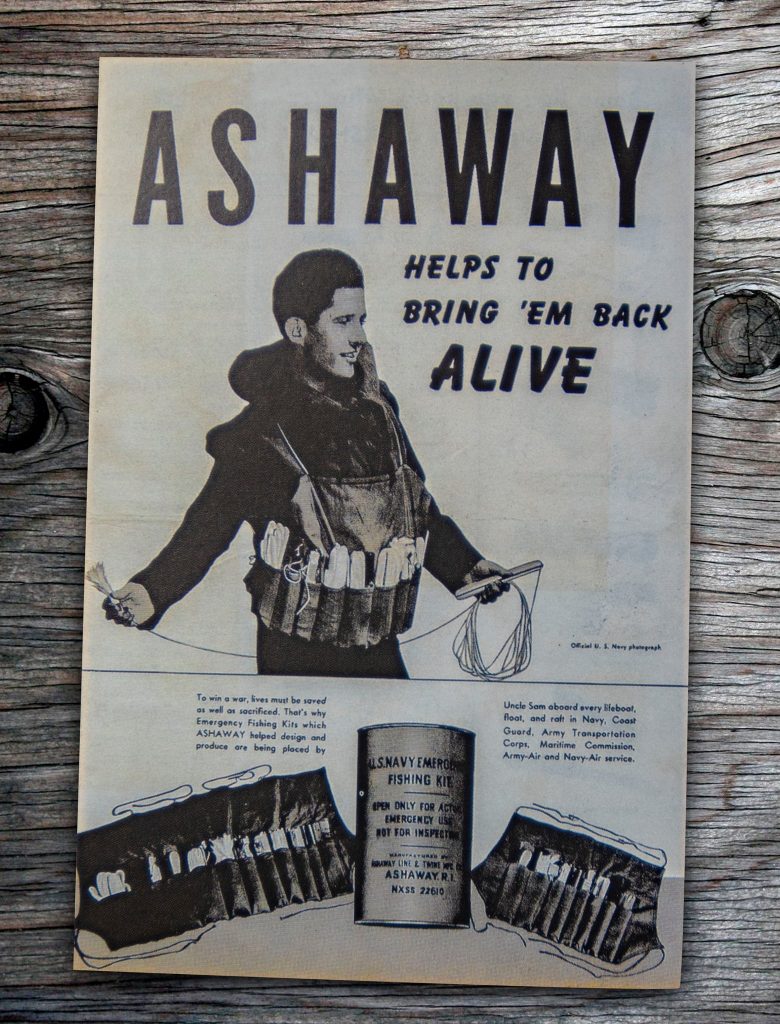

Once approved, the kits were constructed by Julian Crandall and his Ashaway Line & Twine Company in Ashaway, Rhode Island. In short order, they were packed aboard lifeboats and ship’s rafts and began saving lives almost immediately. Literally hundreds of grateful letters were received from servicemen in all theatres, prompting several other Allied nations to adopt the kits and also hastening the development of a smaller kit especially for downed airmen that could be packed aboard an emergency life raft.

The near overnight success of the military survival kits brought enormous acclaim to the IGFA, and this quickly spawned another project. In many remote outposts, wounded servicemen at field hospitals had little to do during their recovery, and patient morale was correspondingly poor. After some consideration, it was decided that taking advantage of local angling opportunities might represent both a welcome distraction and a means of supplementing military rations.

In early 1943, Lerner first proposed the idea of a recreational fishing kit to authorities in Washington DC, but he soon grew frustrated after months of governmental foot-dragging. Determined to see his idea through, he personally financed the development and initial production of what would quickly become a hugely successful morale-builder. The first recreational kits consisted of 100 feet of 30-lb test fishing line, assorted lures, hooks, and sinkers, plus a spearhead, dip net, and instructions printed on waterproof paper. The contents were then wrapped in a twill sleeve and made ready for shipment. Weighing in at a tidy 41 ounces, their worth to wounded servicemen quickly proved more than gold. The IGFA teamed up with the Red Cross to facilitate distribution, and the first 3,000 kits prompted a flood of letters pleading for more.